Welcome to ANTH 1002: Anthropology for a better world

Please come in

- Move to the center of the row to find a seat.

- Help everyone find a place. (Don’t get too settled.)

Lectures in ANTH 1002 will start at 12:05 p.m.

- We meet for 50 minutes and then have a 10 minute break.

- We come back at 1:05 p.m. and then leave at 1:55 p.m.

If you require hearing or other assistance, please sit in the front rows or near the doors.

An outline of this lecture is available online at https://anthrograph.rschram.org/1002/2025/01.

Is it always this busy?

Enrollment in the class is high, so Week 1 will be a bit crazy.

Tutorials will start in Week 2. Everyone enrolled in the class by Tuesday of Week 2 will be allocated a place in a tutorial on Tuesday of Week 2.

Welcome! Let’s get to know each other

I am Ryan Schram. I am the coordinator for ANTH 1002.

Lecturers

- Ryan Schram (weeks 1–4 and 13)

- Shiori Shakuto (weeks 5–7)

- Luis Angosto Ferrandez (weeks 8–10)

- Two special guests, Angela Wong and Duong Tran, will be here for Weeks 11 and 12.

Tutors

Tutorials start in Week 2, where you will meet your tutor. The tutors are:

- Tobias Hansson

- Nkosi Lessey

- Cate Massola

- M Shan E Alam Misty

- Lise Sasaki

- Ume Rubab Sheikh

- Rob Stone

- Angela Wong

- Dennis Venter

Anthropology is the study of what it means to be human, but the human condition isn’t the same everywhere

Anthropology is not like other social sciences. It’s a tool we can use to address urgent problems.

The students who answered my pre-class survey mentioned

- violence, war, and abuse

- poverty, lack of education, disease

- lack of opportunity, discrimination, oppression

- polarization and conflict

- climate change

were the most important problems in the world today. Students in past classes have said many similar things.

Recently, most have been concerned with just one problem—climate change.

Let’s ask a new question.

Let’s talk: What will the world look like in the year 2045?

Stand up, look around, greet the people around you.

Ask the people around you what they think the future holds:

- What will the world be like in 20 years?

- What will be the same? What will be different?

- Will your life and your environment be the same? Will it be better or worse? And other people’s?

In the year 2045, the anthropology department at Sydney will be celebrating its 120th anniversary! Wow! That’s something to look forward to.

Everyone experiences global problems, but not the same way

All the things we could name as urgent crises are global in nature.

But that also means that every person will be grappling with a different part of it, and will experience it in the context of their own lives in a specific place and time.

Consider global warming

Is global warming a problem of

- Massive floods in Pakistan (“Devastating Floods in Pakistan” 2022)

- The possibility of statelessness for people in Tuvalu (Wilson 2025)

- Forced relocation for Indigenous people of Louisiana (Jessee 2022)

- Increasing numbers of grolar bears in Canada (Antonio 2024)

- Schools closing in Singapore because “it’s too hot to think” (Lee 2025)

And, yet, everyone needs to work together even if we don’t agree on what the problem is.

What is anthropology, and what is it good for?

I would like to argue that anthropology—the study of how people live in all its diversity and complexity—has a lot to say about these kinds of big problems.

Anthropology is a science of society, but unlike other social sciences, it tries to help people imagine what is like to live in a particular set of social conditions.

To think like an anthropologist

- You have to give up on what you think is normal. We are professional strangers.

- You have to give up on what you think you know. We learn to listen. The people whom we want to understand are our teachers.

- You have to learn by doing. To see the world from another person’s point of view requires us to share their experiences.

Anthropologists write ethnographies, or qualitative descriptions and interpretations of what life is like for people who live in a specific social situation.

- Ethnographic writing is more than just a description.

- Reading ethnographic writing helps you cultivate an ethnographic imagination.

The future is a foreign country. They do things differently there.

Experts claim that we can find solutions to problems

It is tempting to embrace these kinds of answers, because they come from people who sound like experts.

- It’s usually a simple, one-size-fits-all answer

- But their answers only make sense if we all agree on the problem.

Anthropologists assume they need to learn from other people’s experiences, because knowledge is relative

- We assume we have to take up a different perspective to really understand reality. What anyone knows is always relative to a specific context.

- An ethnographic imagination is helpful for a lot of things, but the biggest thing is that it helps us to realize the limits of our own perspectives.

In an ethnographic imagination, it is possible to think outside of what we believe is normal.

There already are anthropologists at the table

What does “globalization” mean? What if it is not what you learned in high school?

A group of small developing countries led by Vanuatu recently argued before the International Court of Justice as it was considering its advisory opinion on the obligations of states to prevent climate change.

They offered testimony collected from all over the world to document all the different ways people and communities have been harmed by the effects of climate change. Climate change has already created

- Greater poverty

- Greater risk to health

- Lack of freedom to pursue a good life

The ICJ ruled that states do have an obligation to prevent harms to people in other states. This is a new way of talking about what climate change itself is

- Climate change is not a symptom of too much pollution, or even too much economic growth.

In this new way of thinking,

Climate change is the consequence of choices made by powerful actors which violate basic rules about how people should treat each other.

The world as a whole is a community in which people and groups have responsibilities to each other, and have an obligation to make restitution for injuries to others.

Anthropology as “ruthless criticism” (rücksichtslose Kritik)

Anthropology descends from a long tradition of critical thought.

Consider the ideas of “the young Marx”, who believed he and his fellow radicals would change the world with critique (Kritik):

“[A social reformer is] compelled to confess to himself that he has no clear conception of what the future should be. That, however, is just the advantage of the new trend: that we do not attempt dogmatically to prefigure the future, but want to find the new world only through criticism [Kritik] of the old.” (Marx [1843] 1978, 13)

“[W]e realize all the more clearly what we have to accomplish in the present—l am speaking of a ruthless criticism [rücksichtslose Kritik] of everything existing, ruthless in two senses: The criticism must not be afraid of its own conclusions, nor of conflict with the powers that be.” (Marx [1843] 1978, 13)

The mechanics of this class: The weekly cycle

Each week in the class is a conversation: among students, and between each student and their tutor. We repeat the same cycle each week.

- Read the required readings (and, if you want to know more, read recommended readings).

- Think about what they say and what you think of them.

- Write something about what you’ve read, and submit it to your tutor.

- Eat some brain candy. Explore the topic of the week through new media, and see how the week’s issues enter into contemporary cultures.

- Ask questions, discuss, and listen in lecture and tutorial.

- Receive feedback from tutors about your ideas.

- Lather, rinse, repeat…

Weekly writing assignments

To prepare for lecture and tutorial each week, you will submit your answer to an open question.

There are no right answers to these questions. They are not tests. You get a +1 if you submit them on time, by Monday at 11:59 p.m. and simply make a genuine effort to answer the question with your own view.

Think of these weekly writing assignments as a warm-up exercise. They will help you collect your ideas about a topic before class so you can have something to contribute.

These writing assignments also help you think about the readings in preparation for your major writing assignments.

A road map for this semester: The topics we will cover

The class is divided into four 3-week modules. Each focuses on one important topic in anthropology, but together these are just a small sample of the kinds of things that anthropologists study.

Each module is an example of how anthropologists think, and why anthropology matters to understanding the contemporary world.

- The first week examines a big idea in anthropology.

- The second week presents a single ethnographic case study, a qualitative description and analysis of a single situation or community in the real world.

- The third week extends the investigation of the topic by asking how we can turn the lens of anthropology back on ourselves, and examine our own societies and backgrounds as one possibility among many.

Anthropology is never just the study of what other people do. It is always also a search for alternatives. The purpose of examining people’s lives is to rethink what we assume is natural and normal about our own lives.

How to get the assigned readings

Every week we will read work by anthropologists, and all of the selected works we we read are available through the library catalogue in one way or another.

To find the assigned readings, start on the page on the class Canvas site for the upcoming week.

What is Tuvalu worried about?

And here is a link to a map of Tuvalu: https://maps.app.goo.gl/1isyxJY7oipkF3dG9

Imagine Tuvalu in the year 2045. What will it be like?

The choices depend on one’s imagination of the problem

In 2001, the Australian government’s position on Tuvalu was stated as follows:

Australia would join a co-ordinated international response to any environmental disaster. But Tuvaluans could not get special treatment as environmental refugees and would have to apply under the migration program like anyone else. (Wroe 2001)1

In 2007, the Howard government maintained this postion, denying that “environmental refugees” were a legitimate category of migrant, and refusing to meet with Tuvalu representatives (Baker 2007)

In 2011, Australia, New Zealand, and the European Union donated supplies and water tanks to combat a severe drought (Marles 2011).

In 2017, Tuvalu received loans from parties to UN climate treaties for a coastal adaptation project (“Timeline” n.d.).

In 2022, the foreign minister of Tuvalu announced that the country would “build a digital version of itself” in the metaverse to preserve its existence (Craymer 2022).

In 2025, Australia and Tuvalu sign an agreement in which Australia would issue 280 visas per year to people of Tuvalu.

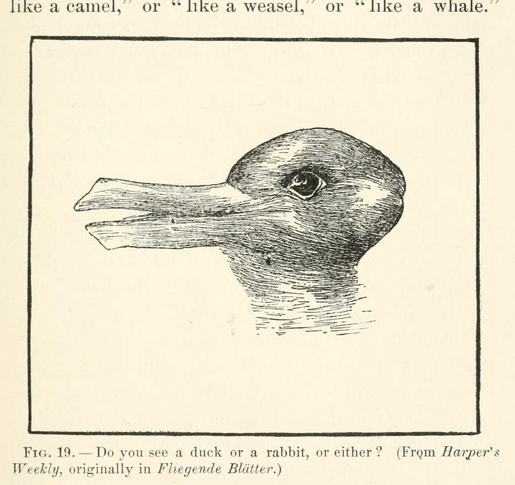

Look again

The reality of society

While anthropologists have many different ways to define society and “the social,” they all have something in common:

- There is no such thing as a society of one. Societies are collectives.

Emile Durkheim is a founding figure of sociology and anthropology

- Prior to Durkheim’s idea of a social science, people thought about society and its order as a question of what should be, that is, as a question of right and wrong.

- Durkheim proposes that we should ask instead what is and why.

- Durkheim states that a society is sui generis—it causes itself (Durkheim [1895] 1982, 144)

- For the same reason, Durkheim states that a society is a whole which is greater than the sum of its parts.

- To study any one thing that people do or experience, we have to see it as part of a larger whole: This is a perspective of holism.

Durkheim’s metaphors of society

If society is a whole which is greater than the sum of its parts, and we’re the parts, then it is an abstract reality that is hard to grasp. You can’t actually see or touch the whole.

Durkheim uses many metaphors to convey his sense of the social

- Society is a machine, and its elements fit together like gears (Durkheim [1895] 1982, 123).

- Society is a body, with distinct organs that are also interdependent (Durkheim [1895] 1982, 121)

- Society is a collective consciousness, a big brain

that thinks for each member of society (Durkheim [1895] 1982, 238).

- We aren’t aware of the thoughts that the big collective social brain thinks. To us, they are our reality. We act as if the thoughts of the collective consciousness are facts.

References

As quoted in Farbotko (2005, 288).↩︎