Look again

Please come in

Lectures in ANTH 1002 will start at 12:05 p.m.

If you require hearing or other assistance, please sit in the front rows or near the doors.

An outline of this lecture is available online at https://anthrograph.rschram.org/1002/2025/01.

Enrollment in the class is high, so Week 1 will be a bit crazy.

Tutorials will start in Week 2. Everyone enrolled in the class by Tuesday of Week 2 will be allocated a place in a tutorial on Tuesday of Week 2.

I am Ryan Schram. I am the coordinator for ANTH 1002.

Tutorials start in Week 2, where you will meet your tutor. The tutors are:

Anthropology is not like other social sciences. It’s a tool we can use to address urgent problems.

The students who answered my pre-class survey mentioned

were the most important problems in the world today. Students in past classes have said many similar things.

Recently, most have been concerned with just one problem—climate change.

Let’s ask a new question.

Stand up, look around, greet the people around you.

Ask the people around you what they think the future holds:

In the year 2045, the anthropology department at Sydney will be celebrating its 120th anniversary! Wow! That’s something to look forward to.

All the things we could name as urgent crises are global in nature.

But that also means that every person will be grappling with a different part of it, and will experience it in the context of their own lives in a specific place and time.

Is global warming a problem of

And, yet, everyone needs to work together even if we don’t agree on what the problem is.

I would like to argue that anthropology—the study of how people live in all its diversity and complexity—has a lot to say about these kinds of big problems.

Anthropology is a science of society, but unlike other social sciences, it tries to help people imagine what is like to live in a particular set of social conditions.

To think like an anthropologist

Anthropologists write ethnographies, or qualitative descriptions and interpretations of what life is like for people who live in a specific social situation.

It is tempting to embrace these kinds of answers, because they come from people who sound like experts.

In an ethnographic imagination, it is possible to think outside of what we believe is normal.

What does “globalization” mean? What if it is not what you learned in high school?

A group of small developing countries led by Vanuatu recently argued before the International Court of Justice as it was considering its advisory opinion on the obligations of states to prevent climate change.

They offered testimony collected from all over the world to document all the different ways people and communities have been harmed by the effects of climate change. Climate change has already created

The ICJ ruled that states do have an obligation to prevent harms to people in other states. This is a new way of talking about what climate change itself is

In this new way of thinking,

Climate change is the consequence of choices made by powerful actors which violate basic rules about how people should treat each other.

The world as a whole is a community in which people and groups have responsibilities to each other, and have an obligation to make restitution for injuries to others.

Anthropology descends from a long tradition of critical thought.

Consider the ideas of “the young Marx”, who believed he and his fellow radicals would change the world with critique (Kritik):

“[A social reformer is] compelled to confess to himself that he has no clear conception of what the future should be. That, however, is just the advantage of the new trend: that we do not attempt dogmatically to prefigure the future, but want to find the new world only through criticism [Kritik] of the old.” (Marx [1843] 1978, 13)

“[W]e realize all the more clearly what we have to accomplish in the present—l am speaking of a ruthless criticism [rücksichtslose Kritik] of everything existing, ruthless in two senses: The criticism must not be afraid of its own conclusions, nor of conflict with the powers that be.” (Marx [1843] 1978, 13)

Each week in the class is a conversation: among students, and between each student and their tutor. We repeat the same cycle each week.

To prepare for lecture and tutorial each week, you will submit your answer to an open question.

There are no right answers to these questions. They are not tests. You get a +1 if you submit them on time, by Monday at 11:59 p.m. and simply make a genuine effort to answer the question with your own view.

Think of these weekly writing assignments as a warm-up exercise. They will help you collect your ideas about a topic before class so you can have something to contribute.

These writing assignments also help you think about the readings in preparation for your major writing assignments.

The class is divided into four 3-week modules. Each focuses on one important topic in anthropology, but together these are just a small sample of the kinds of things that anthropologists study.

Each module is an example of how anthropologists think, and why anthropology matters to understanding the contemporary world.

Anthropology is never just the study of what other people do. It is always also a search for alternatives. The purpose of examining people’s lives is to rethink what we assume is natural and normal about our own lives.

Every week we will read work by anthropologists, and all of the selected works we we read are available through the library catalogue in one way or another.

To find the assigned readings, start on the page on the class Canvas site for the upcoming week.

And here is a link to a map of Tuvalu: https://maps.app.goo.gl/1isyxJY7oipkF3dG9

Imagine Tuvalu in the year 2045. What will it be like?

In 2001, the Australian government’s position on Tuvalu was stated as follows:

Australia would join a co-ordinated international response to any environmental disaster. But Tuvaluans could not get special treatment as environmental refugees and would have to apply under the migration program like anyone else. (Wroe 2001)1

In 2007, the Howard government maintained this postion, denying that “environmental refugees” were a legitimate category of migrant, and refusing to meet with Tuvalu representatives (Baker 2007)

In 2011, Australia, New Zealand, and the European Union donated supplies and water tanks to combat a severe drought (Marles 2011).

In 2017, Tuvalu received loans from parties to UN climate treaties for a coastal adaptation project (“Timeline” n.d.).

In 2022, the foreign minister of Tuvalu announced that the country would “build a digital version of itself” in the metaverse to preserve its existence (Craymer 2022).

In 2025, Australia and Tuvalu sign an agreement in which Australia would issue 280 visas per year to people of Tuvalu.

While anthropologists have many different ways to define society and “the social,” they all have something in common:

Emile Durkheim is a founding figure of sociology and anthropology

If society is a whole which is greater than the sum of its parts, and we’re the parts, then it is an abstract reality that is hard to grasp. You can’t actually see or touch the whole.

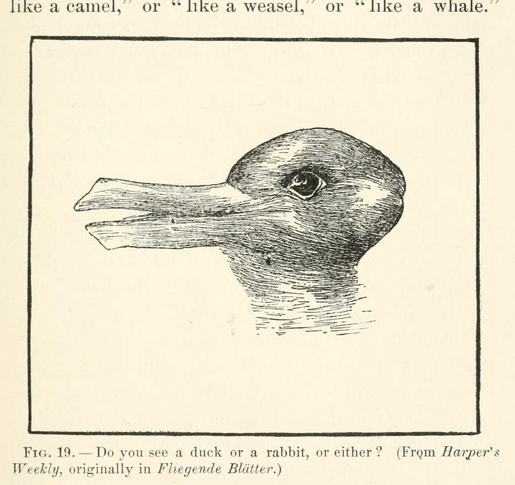

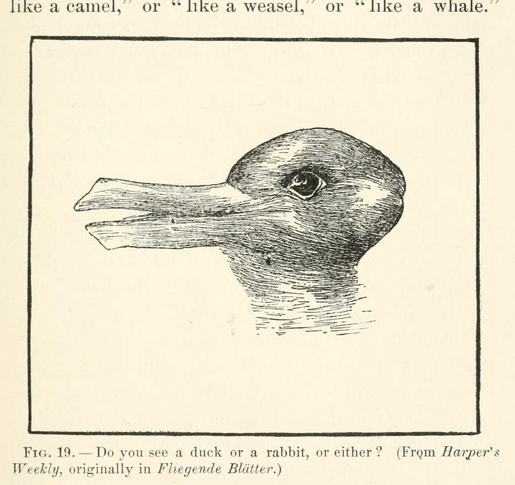

Durkheim uses many metaphors to convey his sense of the social

As quoted in Farbotko (2005, 288).↩︎